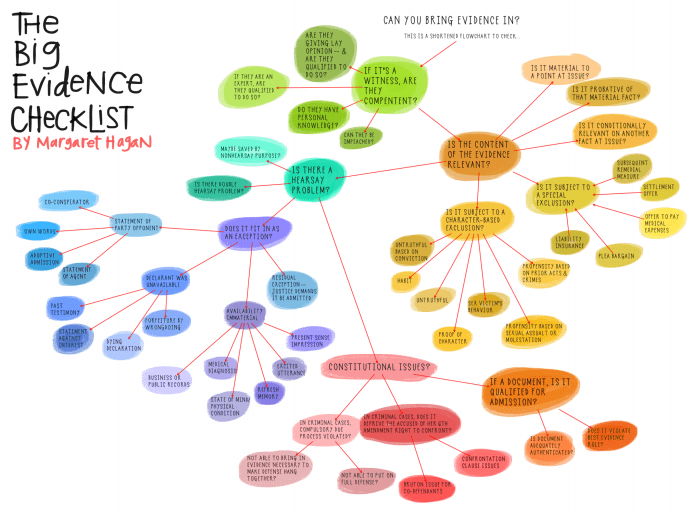

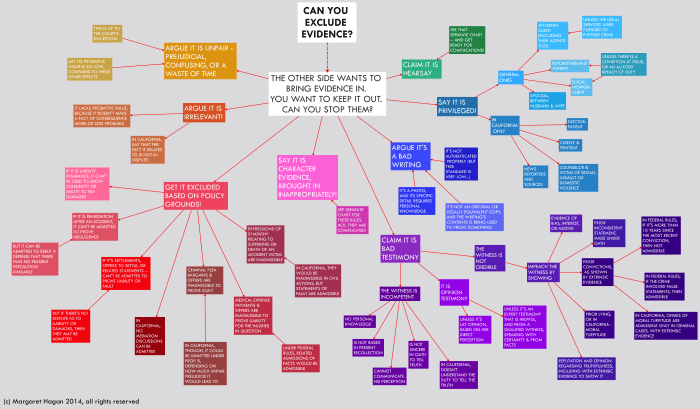

Introducing the Federal Rules of Evidence Flowchart, an indispensable tool for navigating the complex landscape of evidence admissibility in federal courts. This flowchart provides a clear and concise overview of the key provisions of the Federal Rules of Evidence, empowering legal professionals and students alike to effectively analyze and present evidence.

Delving into the intricacies of relevance, hearsay, character evidence, impeachment, privileges, burden of proof, presumptions, expert testimony, scientific evidence, and demonstrative evidence, this flowchart serves as a valuable resource for understanding the foundational principles governing the admissibility of evidence in federal trials.

Introduction

The Federal Rules of Evidence (FRE) are a comprehensive set of rules that govern the admissibility of evidence in federal courts and proceedings. They were developed to ensure the fairness and reliability of trials by establishing uniform standards for the admission of evidence.

The FRE were initially drafted by the Supreme Court’s Advisory Committee on Evidence and were adopted by Congress in 1975. They have since been amended several times to reflect changes in technology and legal precedent.

Purpose of the FRE

The FRE serve several important purposes:

- To ensure that the evidence presented in court is relevant, reliable, and probative.

- To protect the rights of witnesses and parties to the proceedings.

- To promote the fair and efficient administration of justice.

Scope of the FRE

The FRE apply to all civil and criminal proceedings in federal courts, including:

- District courts

- Courts of appeals

- Bankruptcy courts

- Magistrate courts

The FRE also apply to certain proceedings before federal administrative agencies.

Relevance

Relevance is a fundamental concept in the Federal Rules of Evidence. It governs the admissibility of evidence by ensuring that only evidence that has a tendency to make a fact more or less probable is admitted at trial.

The Federal Rules of Evidence define relevance as “evidence having any tendency to make the existence of any fact that is of consequence to the determination of the action more probable or less probable than it would be without the evidence.”

Fed. R. Evid. 401.

Tests for Relevance

There are two main tests for relevance under the Federal Rules of Evidence:

- Logical relevance:This test asks whether the evidence has any tendency to make a fact more or less probable. The fact does not have to be directly related to the ultimate issue in the case, but it must be relevant to some issue that is relevant to the ultimate issue.

- Legal relevance:This test asks whether the evidence is admissible under the rules of evidence. Even if the evidence is logically relevant, it may not be admissible if it is barred by a rule of evidence, such as the hearsay rule or the rule against character evidence.

Examples of Relevant and Irrelevant Evidence

Examples of relevant evidence:

- In a murder trial, evidence that the defendant was seen arguing with the victim shortly before the murder is relevant because it tends to make the fact that the defendant killed the victim more probable.

- In a breach of contract case, evidence that the defendant failed to perform the contract is relevant because it tends to make the fact that the defendant breached the contract more probable.

Examples of irrelevant evidence:

- In a murder trial, evidence that the defendant has a history of violent crime is irrelevant because it does not tend to make the fact that the defendant killed the victim more probable.

- In a breach of contract case, evidence that the defendant is a wealthy person is irrelevant because it does not tend to make the fact that the defendant breached the contract more probable.

Hearsay

The hearsay rule prohibits the admission of out-of-court statements offered to prove the truth of the matter asserted therein unless an exception applies. The rationale for the rule is that out-of-court statements are not subject to the same safeguards as in-court testimony, such as cross-examination.

There are numerous exceptions to the hearsay rule, including:

Excited Utterances

Excited utterances are statements made under the influence of excitement caused by a startling event or condition. These statements are admissible because they are considered to be reliable due to the lack of time for fabrication or deliberation.

Present Sense Impressions

Present sense impressions are statements made while the declarant is perceiving an event or condition. These statements are admissible because they are considered to be reliable due to the lack of time for fabrication or deliberation.

Then-Existing Mental, Emotional, or Physical Condition, Federal rules of evidence flowchart

Statements of then-existing mental, emotional, or physical condition are admissible to prove the declarant’s state of mind at the time the statement was made. These statements are admissible because they are considered to be reliable due to the lack of motive to fabricate.

Admissions of a Party-Opponent

Admissions of a party-opponent are statements made by a party to the lawsuit that are inconsistent with the party’s position in the case. These statements are admissible because they are considered to be reliable due to the party’s interest in the outcome of the case.

Hearsay Within Hearsay

Hearsay within hearsay is a statement that is offered to prove the truth of the matter asserted therein and that contains another hearsay statement. Hearsay within hearsay is generally not admissible unless an exception applies to both the outer and inner hearsay statements.

Examples of Hearsay and Non-Hearsay Statements

- Hearsay:“John told me that he saw Mary rob the bank.” (Offered to prove that Mary robbed the bank)

- Non-hearsay:“John told me that he saw Mary wearing a red dress.” (Offered to prove that Mary was wearing a red dress)

Character Evidence

Character evidence is evidence that is offered to prove that a person acted in a certain way on a particular occasion because that person has a certain character trait. The Federal Rules of Evidence generally prohibit the admission of character evidence, but there are some exceptions to this rule.

The most important exception is the “character in issue” exception. This exception allows the admission of character evidence when a person’s character is an essential element of the crime charged. For example, in a murder case, the prosecution may introduce evidence that the defendant has a history of violence to prove that he is more likely to have committed the murder.

Another exception to the rule against character evidence is the “habit” exception. This exception allows the admission of evidence of a person’s habit to prove that the person acted in a certain way on a particular occasion. For example, in a car accident case, the plaintiff may introduce evidence that the defendant has a habit of running red lights to prove that he is more likely to have run the red light that caused the accident.

Finally, the rule against character evidence does not apply to reputation evidence. Reputation evidence is evidence of a person’s reputation in the community. Reputation evidence is admissible to prove that a person has a certain character trait, but it is not admissible to prove that the person acted in a certain way on a particular occasion.

Types of Character Evidence

- Specific acts evidence: Evidence of a person’s specific acts is generally not admissible to prove that the person has a certain character trait. However, there are some exceptions to this rule. For example, specific acts evidence is admissible to prove a person’s habit or to impeach a witness’s credibility.

- Reputation evidence: Evidence of a person’s reputation in the community is admissible to prove that the person has a certain character trait. However, reputation evidence is not admissible to prove that the person acted in a certain way on a particular occasion.

- Opinion evidence: Opinion evidence is evidence of a person’s opinion about another person’s character. Opinion evidence is generally not admissible to prove that the person has a certain character trait. However, there are some exceptions to this rule. For example, opinion evidence is admissible to impeach a witness’s credibility.

Examples of Admissible and Inadmissible Character Evidence

- Admissible character evidence: In a murder case, the prosecution may introduce evidence that the defendant has a history of violence to prove that he is more likely to have committed the murder.

- Inadmissible character evidence: In a car accident case, the plaintiff may not introduce evidence that the defendant has a habit of speeding to prove that he is more likely to have been speeding when he caused the accident.

Impeachment: Federal Rules Of Evidence Flowchart

Impeachment refers to the process of challenging the credibility of a witness in a legal proceeding. It involves presenting evidence to show that the witness’s testimony is unreliable or untrustworthy.

There are several methods of impeachment, including:

- Contradiction: Introducing evidence that directly contradicts the witness’s testimony.

- Prior Inconsistent Statement: Introducing a statement made by the witness outside of court that is inconsistent with their current testimony.

- Bias: Showing that the witness has a motive to lie or misrepresent the truth.

- Character for Truthfulness: Introducing evidence of the witness’s reputation for truthfulness or lack thereof.

Impeachment evidence can be used to attack the credibility of a witness on specific points or to challenge their overall credibility. The admissibility of impeachment evidence is governed by the Federal Rules of Evidence.

Privileges

Privileges are a fundamental aspect of the Federal Rules of Evidence (FRE) that protect certain communications from disclosure in legal proceedings. These privileges serve to protect important relationships and promote the public interest.

The FRE recognizes several types of privileges, including:

Attorney-Client Privilege

- Protects communications between an attorney and their client that are made in confidence for the purpose of obtaining or providing legal advice.

- Example: A conversation between a lawyer and their client about the details of a criminal case.

Doctor-Patient Privilege

- Protects communications between a healthcare professional and their patient that are made in confidence for the purpose of diagnosis or treatment.

- Example: A conversation between a doctor and their patient about a medical condition.

Spousal Privilege

- Protects confidential communications between spouses that are made during the course of their marriage.

- Example: A conversation between a husband and wife about their financial affairs.

Clergy-Penitent Privilege

- Protects confidential communications between a member of the clergy and their penitent that are made in the context of a religious confession.

- Example: A conversation between a priest and their parishioner during confession.

Journalist’s Privilege

- Protects confidential communications between a journalist and their source that are made in the context of newsgathering.

- Example: A conversation between a reporter and their confidential source about a sensitive news story.

Burden of Proof

The burden of proof refers to the obligation of a party in a legal proceeding to present evidence and persuade the fact-finder (judge or jury) that a particular fact is true.

Under the Federal Rules of Evidence, there are different types of burden of proof, each requiring a different level of persuasion:

Preponderance of the Evidence

The most common burden of proof in civil cases. It requires the party with the burden to prove that a fact is more likely true than not true.

Clear and Convincing Evidence

A higher standard of proof than a preponderance of the evidence. It requires the party with the burden to prove that a fact is highly probable.

Beyond a Reasonable Doubt

The highest standard of proof in criminal cases. It requires the prosecution to prove that the defendant is guilty beyond any reasonable doubt.

Presumptions

Presumptions are rules of law that establish the existence of a particular fact or legal conclusion based on the occurrence of another fact. They shift the burden of proof from one party to another by providing a starting point for the trier of fact (judge or jury).

There are two main types of presumptions:

Rebuttable Presumptions

Rebuttable presumptions can be overcome by presenting evidence to the contrary. For example, the presumption of innocence in criminal cases can be rebutted by the prosecution presenting evidence of guilt.

Conclusive Presumptions

Conclusive presumptions cannot be rebutted and are treated as conclusively true. For example, the presumption of regularity in official proceedings (e.g., that public officials have properly performed their duties) is a conclusive presumption.

Presumptions can be created by statute, common law, or judicial decision. Some examples of presumptions include:

- The presumption of innocence in criminal cases

- The presumption of sanity

- The presumption of regularity in official proceedings

- The presumption of legitimacy of a child born to a married woman

Expert Testimony

Expert testimony is admissible if it is relevant, reliable, and helpful to the jury. Courts consider several factors in determining whether to admit expert testimony, including the expert’s qualifications, the basis for the expert’s opinion, and the likelihood that the expert’s testimony will be helpful to the jury.

Qualifications

An expert witness must be qualified to testify on the subject matter of his or her testimony. The expert’s qualifications can be based on education, training, experience, or a combination of these factors.

Basis for Opinion

The expert’s opinion must be based on reliable and scientifically valid methods. The expert must be able to explain the basis for his or her opinion and must be able to support it with data or other evidence.

Helpful to the Jury

The expert’s testimony must be helpful to the jury. The expert’s testimony must be clear, concise, and understandable. The expert must be able to communicate his or her findings in a way that the jury can understand.

Examples of Admissible Expert Testimony

* A medical doctor can testify about the cause of a patient’s death.

- A psychologist can testify about the mental state of a defendant.

- An economist can testify about the economic impact of a proposed law.

Examples of Inadmissible Expert Testimony

* A witness who is not a medical doctor cannot testify about the cause of a patient’s death.

- A witness who is not a psychologist cannot testify about the mental state of a defendant.

- A witness who is not an economist cannot testify about the economic impact of a proposed law.

Scientific Evidence

Scientific evidence plays a significant role in the legal process, particularly in cases involving complex scientific issues. The admissibility of scientific evidence is governed by specific rules and standards to ensure its reliability and relevance.

Courts consider several factors in determining whether to admit scientific evidence, including:

- Whether the scientific method was properly applied

- Whether the scientific theory or technique is generally accepted within the relevant scientific community

- Whether the scientific evidence is relevant to the case and will assist the trier of fact in understanding the evidence or determining a fact in issue

- Whether the probative value of the scientific evidence outweighs its prejudicial effect

Examples of Admissible Scientific Evidence

Examples of admissible scientific evidence include:

- DNA evidence to establish identity or exclude a suspect

- Forensic analysis to determine the cause of death or the time of death

- Medical expert testimony to explain the effects of an injury or illness

Examples of Inadmissible Scientific Evidence

Examples of inadmissible scientific evidence include:

- Polygraph test results

- Hypnosis-induced testimony

- Unscientific or speculative theories

Demonstrative Evidence

Demonstrative evidence is physical evidence that is used to illustrate or clarify other evidence. It is admissible if it is relevant, authentic, and not misleading. The most common types of demonstrative evidence include:

- Photographs

- Documents

- Models

- Maps

- Charts

Demonstrative evidence can be used to prove a variety of facts, such as the identity of a person or object, the location of an event, or the condition of a place or thing. It can also be used to illustrate the testimony of a witness or to help the jury understand a complex issue.

The admissibility of demonstrative evidence is governed by the Federal Rules of Evidence (FRE). FRE 403 provides that all relevant evidence is admissible unless its probative value is substantially outweighed by the danger of unfair prejudice, confusion of the issues, or misleading the jury.

In order to be admissible, demonstrative evidence must be:

- Relevant to the case

- Authentic

- Not misleading

If the demonstrative evidence meets these requirements, it will be admitted into evidence. However, if the evidence does not meet these requirements, it will be excluded.

Examples of Admissible and Inadmissible Demonstrative Evidence

The following are examples of admissible demonstrative evidence:

- A photograph of the crime scene

- A document that was signed by the defendant

- A model of the human body

- A map of the area where the crime occurred

- A chart that shows the defendant’s financial history

The following are examples of inadmissible demonstrative evidence:

- A photograph that is not relevant to the case

- A document that is not authentic

- A model that is not accurate

- A map that is not to scale

- A chart that is misleading

Conclusion

The Federal Rules of Evidence (FRE) provide a comprehensive framework for the admissibility of evidence in federal courts. They are designed to ensure the fairness and reliability of trials by ensuring that only relevant and reliable evidence is admitted.

The FRE are divided into 11 articles, each of which covers a different aspect of evidence law. The articles cover topics such as relevance, hearsay, character evidence, impeachment, privileges, burden of proof, presumptions, expert testimony, scientific evidence, and demonstrative evidence.

Importance of the FRE

The FRE are essential for ensuring the fairness and reliability of trials. They help to ensure that only relevant and reliable evidence is admitted, and that the evidence is presented in a way that is fair to both sides.

The FRE also promote uniformity in the application of evidence law. They ensure that the same rules of evidence are applied in all federal courts, regardless of the jurisdiction.

Recommendations for Further Study

The FRE are a complex and ever-changing body of law. It is important for attorneys to stay up-to-date on the latest changes to the FRE. There are a number of resources available to help attorneys learn more about the FRE, including:

- The Federal Judicial Center

- The American Bar Association

- The National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers

Answers to Common Questions

What is the purpose of the Federal Rules of Evidence?

The Federal Rules of Evidence establish uniform rules for the admissibility of evidence in federal courts, ensuring fairness, reliability, and efficiency in the trial process.

What are the key provisions of the Federal Rules of Evidence?

The Federal Rules of Evidence cover a wide range of topics, including relevance, hearsay, character evidence, impeachment, privileges, burden of proof, presumptions, expert testimony, scientific evidence, and demonstrative evidence.

How can I use the Federal Rules of Evidence Flowchart?

The Federal Rules of Evidence Flowchart provides a visual representation of the key provisions of the Federal Rules of Evidence, making it easy to navigate and understand the complex rules governing evidence admissibility.